Apparently there’s another round of chick-lit wars raging, if this Salon article, “What’s the difference between ‘chick’lit’ and literary fiction?,” is any hint. Some authors embrace the term “chick-lit,” some authors, like Adelle Waldman, run from the label as if they’re being chased by lions on the Serengeti.

I couldn’t care less what an author wants to call her fiction. Rather, I care about the characters in those novels—or I want to. And when you decry “readers’ and journalists’ interests in ‘likable characters'” I’m guessing you don’t want me to care about your characters, in which case, I probably won’t.

Waldman’s self-analysis gets at the heart of a debate that has consumed literary circles this year — one set off when Claire Messud, speaking about her book “The Woman Upstairs” with Publisher’s Weekly, decried readers’ and journalists’ interest in “likable characters.”

And the article goes on to quote Waldman:

“I didn’t want to write a book with a plucky heroine,” said Waldman. “I think a lot of novels operate in a world with a hero or heroine who’s in some ways an underdog and you’re rooting for them. If it’s a heroine getting rid of a bad boyfriend and finding meaningful work and self-esteem, that’s fine, I think. But I wanted my book to operate differently. We’d all like to see ourselves as a hero or heroine of a romantic comedy, but I don’t think that accurately gets at how life really is.”

Thanks for permission to write about a heroine getting rid of a bad boyfriend, Adelle. I’ve done that, once or twice, and it feels great. What’s more, I really like to root for the main character in a novel. In other words, I like to like her. (Or him—men aren’t always bad!) In fact, I won’t read a book if there’s no one to root for, no character that I like enough to spend hours curled up in bed with. And while I like books that are realistic, that describe the world as I know it to be, too much real life, with its aches and unresolved pain, isn’t for me. Why do I want to read about, say, a painful divorce that involves characters I don’t care about? (Heck, I didn’t like living through that when it involved characters I did care about—my parents.)

I’m not sure, though, that the word “likable” is really what she’s going for (or that Claire Messud, in the PW article referenced above, means). There’s a difference between “flawed” and “unlikable.” Creating a flawed character who’s still likable is not easy—and some readers will balk at flaws others will find perfectly acceptable. (I found this out when I started reading my reviews, some of which hated my main character, while others found her flaws believable and wrenching.) But refusing to create a likable character simply because you don’t want to provide your readers with a “friend” is just, well, odd.

Here’s Claire Messud, answering the interviewer who asks: “I wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you? Her outlook is almost unbearably grim.”

For heaven’s sake, what kind of question is that? Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert? Would you want to be friends with Mickey Sabbath? Saleem Sinai? Hamlet? Krapp? Oedipus? Oscar Wao? Antigone? Raskolnikov? Any of the characters in The Corrections? Any of the characters in Infinite Jest? Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written? Or Martin Amis? Or Orhan Pamuk? Or Alice Munro, for that matter? If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t “is this a potential friend for me?” but “is this character alive?”

Jeez. Lighten up!

But then she tells us this about Nora:

Nora’s outlook isn’t “unbearably grim” at all. Nora is telling her story in the immediate wake of an enormous betrayal by a friend she has loved dearly.

Wait…that sounds like a character I can like. I can at least feel sympathy, which is the first step toward liking. And maybe, if I feel she’s justified in her actions (I haven’t read Nora’s story, not even a synopsis) then maybe I’ll continue to like her, despite her flawed behavior.

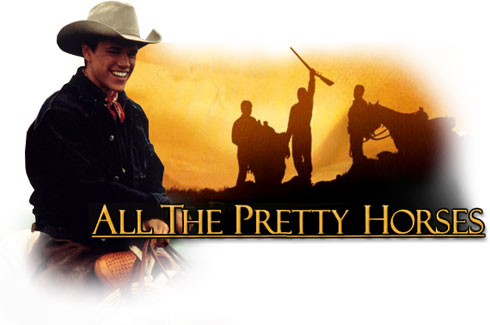

When an author takes such great pains to avoid being seen as writing likable characters, I’m already halfway convinced I don’t want to read their books. (And no, so-called “literary” writers don’t get a pass. One of my favorite characters of all time is John Grady Cole from All the Pretty Horses. I loved him to bits even before Matt Damon played him in the film.)

I don’t like to take life too seriously. I don’t like to take my fiction too seriously, either. And authors who take themselves too seriously—well, I probably wouldn’t want to be their, uh, friend.

Back to Waldman:

“To me, the novels I like and am counting in the serious fiction category would, I hope, try to be very honest about how people are,” Adelle Waldman told Salon, “and less concerned with providing escapist pleasures and more concerned with providing the pleasures of incisive analysis — and maybe humor.”

I think, here, Waldman is using the term “escapist pleasures” as code for “chick-lit” which is of course a fluffy frosting for the word “romance.” But I’ve read plenty of romance, even chick-lit, that provides the “pleasures of incisive analysis” along with humor. Jane Austen, who pretty much invented the romance genre, has plenty of incisive analysis about the plight of women in the 18th century, the conflict between social classes, the dilemma of a parent with five daughters…and modern romances have similar analysis. Judith Ivory’s Pygmalian story The Proposition about a ratcatcher who is groomed to be a gentleman at the hands of a linguist and “manners teacher” comes to mind, as does her story Bliss (written as Judy Cuevas) about a drug addicted French blue-blood who is redeemed by, yes, the love of a good (but flawed!) woman.

(Flawed characters tend to be better at delivering incisive analysis, in my opinion.)

Making I’m making too much of this (thus violating my rule to not take life too seriously, above). I guess I’d really like to head off this latest skirmish in the chick-lit wars. As Rodney King (a flawed but likable character if ever there was one) said, “Can we all just get along?”

https://www.rebelmouse.com/

September 16, 2014 at 12:30 am (11 years ago)Do you have a spam problem on this blog; I also am

a blogger, and I was curious about your situation; wwe hqve developed some nice procedures and we are looking

too swap solutions with others, bee sure to shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Haley

September 22, 2014 at 6:43 pm (11 years ago)Currently iit sounds like WordPress is the

preferred bloogging platform available right now.

(from what I’ve read) Is thast what you are using on your blog?

Antonetta

March 7, 2015 at 4:37 pm (11 years ago)Hello blogger, i found this post on 19 spot in google’s search results.

I’m sure that your low rankings are caused by high bounce rate.

This is very important ranking factor. One of the biggest reason for high bounce rate is due

to visitors hitting the back button. The higher your bounce rate the further down the search results your posts and pages will end up, so

having reasonably low bounce rate is important for improving your rankings naturally.

There is very handy wp plugin which can help you. Just search in google for:

Seyiny’s Bounce Plugin